The Motherless Club

Most people will experience the loss of their mother at some point in their lives and most will cry at the loss of someone they at least at some time in their life, bonded with. I have spent my life trying to understand the biological mother I never bonded with.

Most people will experience the loss of their mother at some point in their lives and most will cry at the loss of someone they at least at some time in their life, bonded with. I have spent my life trying to understand the biological mother I never bonded with.

It’s not that I bonded with as a baby and we later had some irreversible falling out. It’s not that I resent her, though psychopathy, addiction, narcissistic and borderline personality disorders are not easy to like! It’s not that I didn’t have brief phases in my life where I didn’t pressure myself to at least try and go through the motions with her, acquaint myself with the person she was, or ask myself if there was some ‘real mother’ in there somewhere. It wasn’t that I couldn’t find some dissociated part of myself or alter that was capable of forgiving abuse, neglect, trauma, for among the 14 alters in my DID system, I certainly had at least one pleaser and one doormat and one who adapted to our life by practicing absolute neutrality at all times. But even those three simply found her redundant. She’d been replaced before she even started.

Her relationship with me was that of nemesis even before I was born. The second child, a girl, born 16 months after the first born boy to a woman with HUGE issues about girls, her solution had been Quinine. Quinine was a DIY abortion strategy in the 60s which can cause kidney and liver failure but also causes nervous system damage to the unborn child. When it didn’t work the first time, she tried it a second time. I was obviously a weed.

After I was born she probably was dealing with post natal depression, which is hard enough for a human being but probably harder in one who was already a personality disordered drunk with a history of bullying and psychopathy. I spent my first 6 months in a mainly dark room where my father, aunt and grandmother bravely defied commands to not speak to me, not pick me up, not change or feed me. By five months of age I had Rickets, jaundice and recurrent infections. By six months old I’d been thrown through the bedroom window and was now in a program for at risk kids run by a welfare centre where I’d spend my day times until I was two and a half years old.

I bonded with people: my father whose car I felt I grew up in, his parents who lived in our shed in the backyard until I was four and a half, the Italian lady at the end of the street whose gate my pram had been left inside of since I was six months old, and Sister Jellie who ran the welfare program. But all these bonds were severed by the time I was four and a half, except, to a degree, the one with my father, which lasted to his death and beyond regardless of his own madness, lifestyle and its effects.

The program was designed to keep at risk kids out of fostercare by giving the mothers a chance to recover and develop. But my mother had never been mothered. Her mother was a teenager with the first child at age 14 and her at 16 ahead of the next 7. Her parents were alcoholics soon enough, poor, itinerant, ignorant, alcoholic. Her mother’s mother, an alcoholic, had died not long after having her – from peritonitis – and she’d been brought up by her siblings. So even her best efforts to connect bottomed out as “narcissist experiments with its narcissistic object” or “borderline parent plays out with the baby as its scapegoat or resented as its failed carer” or “cash strapped drunk and compulsive gambler explores the uses of child as a means to an end”. In other words, whatever piecemeal efforts there may have been in between, there was no consistency, nothing integral, nothing trustworthy with which I could bond.

She was with a partner who never intended to have a family and showed no interest in more than lipservice to monogamy and the pair of them were as frightening together as anything I’ve ever seen walk onto the Jerry Springer Show. It was hard to tell who was taking down the loaded gun and firing it, who started smashing things, who threw the first punches, but I know who tended to end them – my father. And I know who utilised the battered wife image for all the Valium it could get from the GP – my mother. So between the two of them, they honed a lot of necessary neutrality in me.

I grew up watching other people having functional mothers, mothers they had at least some bonding with. Some kids generously shared their mothers with me, short lived but really important role models. Every year mother’s day comes and goes and I would get the inevitable call by a co-dependent relative to remind me that I have a biological mother, as if somehow going through the motions with someone I have no early bonding with, who I associate with a DID level of trauma, abuse and neglect, is somehow going to become some transformative life changing experience because US self help guru Louise Hay says so.

I AM glad my biological mother was who she was. It did help make me who I am. Any nemesis does. And she inadvertently highlighted all that was of value in those I did bond with, another essential role of a nemesis. And for these things, I feel grateful, not to her, because she did none of that by intention, only default, but to life and the roll of the dice and what it gave me. I like who I am, I like the life I’ve made with that. I have no idea what it is to be born to someone else, the developmental, mental and physical health issues I may never have had born to someone else. I was born to her. And she may muse or experiment in her own world with all she might have been if and if and if, but I’m not her experiment, I never identified with being the narcissistic object she saw and have no interest in being one for her, or anyone who has no emotional equipment to really ‘get’ that we are in fact not objects at all, nor is life a show, or a movie or a chance to play act and indulge, enjoy or learn from the role playing. That’s what you do with dolls. You can buy them on eBay cheaply enough. If you need an adult one you can buy a mannequin and play out to your heart’s content. Dolls and mannequins don’t have souls, their development, mind, emotions, bodies aren’t breakable in the same way as human beings.

One of the hardest things about having a living mother who you have never bonded with and need for your own developmental, mental, emotional and physical health to sustain no contact with, is that you are, essentially, motherless. In my teens I came to understand I was a member of ‘the motherless club’, those of us with living mothers who, nevertheless, had no bonding with whatsoever and, sometimes, additionally had to stay distant from for our own sanity, safety and health.

Harder still is that those biological mothers may have quite different histories with our siblings. They may have emotional incest with them, may have developed entrenched co-dependent relationships they don’t distinguish from love, the sibling may have protectively become the mother’s carer, minder or emotionally parent them or even developed a kind of siblingship with the emotionally needy mother. And so, from a completely different space, they may never have the capacity to understand what essentially amounts to different, even irreconcilable worlds.

Donna Williams, BA Hons, Dip Ed.

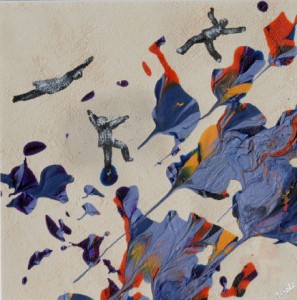

Author, artist, singer-songwriter, screenwriter.

Autism consultant and public speaker.

http://www.donnawilliams.net

I acknowledge Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people as the Traditional Owners of this country throughout Australia, and their connection to land and community.