Life with a Central Hypoventilation Syndrome

WHAT DOES IT MEAN?

Central hypoventilation means your brain keeps forgetting to keep you breathing. See, we have this thing called a ‘respiratory drive’ and this makes us keep breathing. This is why we don’t easily ‘just die’, because there are two things keep us alive; a beating heart and a respiratory drive. If either of those fail partially then we will have problems.

WHAT MIGHT IT LOOK LIKE?

We might look pale, even greyish or have episodes of even moving from grey to blue. We might find ourselves dizzy with problems with circulation to our brain, our hands, our feet, the color having ‘drained from our face’. We may seem ‘out of it’, have ongoing ‘fuzzy headedness’ or ‘brain fog’ from poor blood oxygen levels, or information processing or developmental problems that present as learning difficulties, developmental disability and then associated behavioural challenges.

WHO DOES IT EFFECT?

There are different causes of hypoventilation syndromes in young children. Some examples are metabolism disorders effecting electrolytes and particularly blood sodium levels that can cause problems with the signalling of autonomic messages (heart, breathing, bladder, bowel, temperature, circulation, blood pressure, swallowing reflexes, muscle function), neuromuscular disorders effecting the muscles involved in breathing, genetic disorders like Congenital Central Hypoventilation Syndrome which causes things like Sudden Infant Death Syndrome (SIDS), Prader Willi Syndrome, brain tumor, cervical spinal injury, acute brain poisoning, traumatic brain injury, encephalitis from bacterial or viral infection, asphyxiation or infant stroke from a variety of causes, including asphyxiation.

Respiratory failure also occurs in adults with hypothyroidism, MS, in Parkinsons, in Lou Gehrig’s Disease/ALS/motor neurone disease. It even can occur naturally in elderly people in their 90s, even sometimes as young as in their 80s where degeneration of muscle spindle, stretch reflexes and associated chemoreceptors in the lungs progressively fail in the messaging regarding the body’s state of oxygen and CO2.

HOW COMMON IS CENTRAL HYPOVENTILATION?

Central apnea and central hypoventilation are rare. Only 5% of apnea patients have this form. It is not treated with the same, more common machine used for obstructive apnea where the person has a normal respiratory drive and fights in their sleep for breath. Without a respiratory drive I don’t fight to breathe, the machine fights for me all night, both with inhalation and with exhalation (in my sleep I also don’t exhale without support).

A bilevel machine is essentially assisting both air coming in and facilitating the ability to also expel air. Its like a machine that does CPR on you all night. I take over from the machine for a few minutes once every 30 min to once every 2.5 hours. People die if they fail to breathe for more than 5 minutes.

NATURE OR ENVIRONMENTAL INSULT?

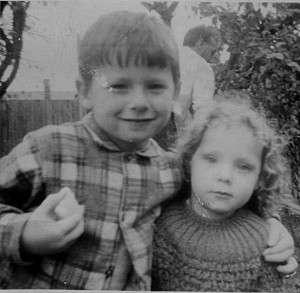

I had subclinical acquired central hypoventilation since age 2-3 which meant that my brain kept forgetting to keep me breathing. I had a series of brain insults starting before I was born and in my first three years. Most particularly between age 2-4 when I had been regularly given gin and valium and enduring suffocation abuse by a disturbed parent.

I had subclinical acquired central hypoventilation since age 2-3 which meant that my brain kept forgetting to keep me breathing. I had a series of brain insults starting before I was born and in my first three years. Most particularly between age 2-4 when I had been regularly given gin and valium and enduring suffocation abuse by a disturbed parent.

However, it is also the case that I have a rare genetic collagen disorder – Ehlers Danlos Syndrome types III/IV – which effect every aspect of connective tissue integrity and function and collagen role within the body, brain and immune system. In the case of EDSIII this includes the integrity of muscle spindles and stretch reflexes, which will include those of the lungs the functioning of chemoreceptors that receive and transmit messages about oxygen and CO2 levels. As the collagen of children with EDSIII progressively fails, they face a range of connective tissue related challenges, potentially even those progressively effecting respiratory drive. It may even be that the kinds of loss of respiratory drive in 90 year olds may be seen decades earlier in adults with EDSIII. We don’t yet know as the diagnosis of this collagen disorder is in its infancy. GPs know little about it, few specialists have any idea about it, and those who have specialised in it are both few and far between and in the early days of still discovering its range and the diffability in the severity of manifestations.

Because of my impaired respiratory drive, I had episodes of turning blue (cyanosis), struggled with feeling light headed, dizzy, and in a daze (somnolence). But it wasn’t until adulthood in 2009 that I began to get concerned enough about it that I told the GP and not until 2012 that I was diagnosed through a sleep study with severe mixed (mostly central) apnea. After genetic testing ruled out the genetic congenital condition of CCHS, one of the only currently known genetic cause of central hypoventilation, we ultimately concluded it was acquired central hypoventilation that had started out as subclinical but worsened with further health events in adulthood.

Because of my impaired respiratory drive, I had episodes of turning blue (cyanosis), struggled with feeling light headed, dizzy, and in a daze (somnolence). But it wasn’t until adulthood in 2009 that I began to get concerned enough about it that I told the GP and not until 2012 that I was diagnosed through a sleep study with severe mixed (mostly central) apnea. After genetic testing ruled out the genetic congenital condition of CCHS, one of the only currently known genetic cause of central hypoventilation, we ultimately concluded it was acquired central hypoventilation that had started out as subclinical but worsened with further health events in adulthood.

Of course the alternative scenario is that as a child with EDSIII/IV I had genetically dodgy collagen which would progressively impact all connective tissue throughout my body: joints, muscles, ligaments, but also the walls of my organs, my vascular system, my skin, even brain connectivity and immune regulation. But theoretically it would also effect the messaging systems between muscle spindles and their stretch receptors including those in the lungs which would degenerate sooner than in the general population, theoretically even starting by early childhood and be significantly noticeable even decades earlier than may present naturally in some of the very elderly experiencing natural age related collagen degeneration and its respiratory and other complications.

Of course, sometimes more than one road leads to ‘Rome’ and something may be a matter of both the chicken and the egg.

WHAT DOES A CLINICAL LEVEL OF CENTRAL HYPOVENTILATION MEAN FOR DAILY LIFE?

The long and the short of it is that since 2012 I have been on bilevel ventilation which means I cannot fall asleep without a breathing machine. This means I can’t fall asleep in a bath, on the sofa, in car seat, on a plane without mechanical ventilation. If I do, my brain will not get the message to keep breathing. At present during sleep I take over breathing for a few seconds every 30 minutes to once every 2.5 hours. The rest is done by the machine.

The long and the short of it is that since 2012 I have been on bilevel ventilation which means I cannot fall asleep without a breathing machine. This means I can’t fall asleep in a bath, on the sofa, in car seat, on a plane without mechanical ventilation. If I do, my brain will not get the message to keep breathing. At present during sleep I take over breathing for a few seconds every 30 minutes to once every 2.5 hours. The rest is done by the machine.

WHAT WOULD HAPPEN IF I FELL ASLEEP WITHOUT MY MECHANICAL VENTILATION?

I have already had a sneak preview of what will happen if I fall asleep without mechanical ventilation for more than a few minutes. I did this accidentally earlier this year. I fell asleep for a few minutes without my mask on. Without a respiratory drive to wake me I went hypoxic and was woken up not by the urgency to breathe but by the oddity of a buzzing vibrating sensation in my chest. As I woke I realised this was coming from my heart and that I did not have a recognisable heart beat. I immediately put on my mask and ventilation which got me into a breathing rhythm and my heart beat returned at first in tachycardia and then levelled out. I asked the GP what I’d experienced and he told me I had gone into atrial fibrillation. I asked what would have happened if the buzzing/vibrating sensation hadn’t woken me. He told me my heart would next have stopped, the oxygen to my brain would then have stopped and I’d die in my sleep.

DOES CLINICAL CENTRAL HYPOVENTILATION RESTRICT ME?

I have two bilevel machines. One for sleeping and one that is portable with a 4 hour battery and allows me to go on a lengthy trip in the car or watch a movie at home and not worry I may snooze. But the days of long haul flights as an international public speaker are over. Quite simply these machines are $4000 each to replace. It would take 2 weeks of approvals and paperwork to even take my machine on the plane for a flights and ensure I could use it during the flight. Then if it got damaged by customs or in the scanner, I would have to spend my nights in an Intensive Care Ward of a hospital where they had a bilevel machine to ensure I could breathe whilst asleep until such time as I got another working machine.

Because this machine is not common its not a matter of going down the local High Street in any city and buying this machine off the shelf. It would usually have to be ordered in, which would take around 2-4 weeks during which time I’d have to stay living in the local hospital.

Even if its only a small risk that I’d find myself without my machine… if you think I should take that risk, then no problem, give me a blindfold and I’ll blind fold you before pushing you out into traffic. After all most cars will probably avoid hitting you and you’ll probably get to the side just fine. You get the idea.

HOW HAS IT EFFECTED MY SENSE OF SELF?

I am happy with my life. Bodies ultimately fail in one way or another. This was how mine did.

I am happy with my life. Bodies ultimately fail in one way or another. This was how mine did.

AM I ILL?

I do not see myself as ill. Nor am I dying. If you met me you’d think ‘she’s a fairly healthy person’ and I’d agree with you completely. But I still won’t fly to your country to give a presentation, accept an award, attend an event or even go to your wedding or your funeral. I can, however be there ‘in person’ via skype. And for me, this is good enough.

Donna Williams, BA Hons, Dip Ed.

Author, artist,and presenter.

http://www.donnawilliams.net

I acknowledge Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people as the Traditional Owners of this country throughout Australia, and their connection to land and community.

Hi! I have some sort of acquired central hypopnea. A recent hospital stay finallly documented that it’s not just during sleep, showing my br/m at 16-18 except when it was 10-11. Not in your league, but I can get pretty hypoxic if the ongoing count in the back of my head (in, two, three) is paused for any reason. I usually notice something is going in when my ox sat hits the mid-80s.

I have a bipap, since my sleep study nearly a decade back, and I do a lot better when I use it. I’ve always woken up, even when I didn’t — but sometimes, that’s been full of adrenaline and gasping for breath in the middle of the night.

hi Ginny, nice to meet you. I don’t fight for breath so when I woke up with numb hands and feet and the chunky headed thing of hypoxia what spooked me more was no natural drive to breathe,… I just sat there for a moment wondering what this was and why my brain wasn’t making me breathe. This was pretty much the same as when I drowned twice at age 3, each time just sank and sat there on the bottom getting dizzier. Glad your hypoxia is at least waking you but your alarm seems a good thing. I do get the tachycardia in a long apnea/hyponea and those likely wake me. Just none of the gasping. But I have slept through to atrial fibrilation once when I accidently fell asleep without my ventilation… taught me a lesson to be far more militant… no snoozing ever without ventilation, not even for a minute because I won’t know if I fall asleep. Re daytime hyponeas maybe check out the respiratory muscles. Saw the Osteopath yesterday and the muscles that work the left side of my ribcage were all in spasm… stuck, like rocks, had no idea (but have had it before), but once he started getting them moving again it was very painful and pinchy, so I think any significant muscular dramas of the respiratory and abdominal muscles may also contribute to daytime hypoventilation. Do you deal with muscle fatigue and spasms? I’m in the process of getting some of this checked out as I suddenly got double vision and a non working eye muscle a few weeks ago, then the other eye started twitching and closing to add to the circus. Have you tried salt for autonomic dysfunction? Helps me with daytime hypoventilation… good for messaging of autonomic nerves… salt attracts water to the cells which helps messaging.